By Stephanie Bennett

The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers Museum (Royal Warwickshire)

The Victoria Cross is the highest gallantry medal awarded by the British monarch to the Armed Forces. From the outset in January 1856 when the medal was created it was awarded to everybody from soldiers to officers regardless of rank. It is truly egalitarian in nature and wholly awarded on merit – For Valour.

It seems to be true that very brave men do extraordinary deeds, and yet they are often very normal and modest people. They appear to be everyday people, just like you and me. If you talked to them you would never know what they had done. Corporal William Amey seems to have been one such person.

He was born in Duddeston, Nechells in the Aston area of Birmingham on the 5th March 1881. William was one of eight children; he had four brothers and three sisters and was the second youngest member of the family. In 1911 William still lived at the parental home at 58 Stella Street, Aston. As a single man of 30 years old, this was normal – households tended to be larger and families stayed together more than today. Elizabeth, the mother, at 69 years old was the head of the household and a widow. Charles her husband who was five years older than her had died in 1909. The eldest son, Charles Henry moved out once he got married, but died in 1911. Walter, aged 42, was a general labourer. Annie and Nellie 38 and 35 years old, were a metal burnisher and servant respectively. Harry 32 was a brass worker and Sidney 27 was an insurance clerk. His youngest brother served in World War I with the Worcestershire Regiment. It was maybe a coincidence that most of the siblings married quite late if at all, rather than when they were younger as was more usual at the time. William was a chandelier maker for Verity’s Limited, electrical manufacturers, at their Plume works in Aston. Birmingham has changed a lot over the years. At the time Aston was really an outer suburb and was only included within the city boundary in 1911.

His love life reads a bit like a modern soap opera. The love of his life was Evelyn (‘Eve’) Matilda (nee Gambles). It seems that they met when they both lived in the Aston area of Birmingham before the outbreak of the Great War. At the time she was married to Frederick Andrew Haines. During this period, it was harder, more unusual and expensive than today to get a divorce (less socially acceptable). As a result, in the 1920’s Eve and William moved to 13 Lansdowne Terrace in Leamington Spa (but stayed on the electoral register for Washwood Heath Ward, Erdington, Birmingham). Evelyn’s first husband then later lived with another woman, and when Frederick died in December 1937 he left his possessions to her, rather than his wife. Finally, officially able to marry, William and Evelyn tied the knot in Edmonton in Essex in the autumn of 1938. The couple settled down in 13 Willes Road, Leamington Spa. In his own quiet way, William must have been proud of his award for Valour, as they named their house ‘Landrecies’ after the place where he won his Victoria Cross.

He served with the 1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, which was based at Aston Manor, Birmingham. It was a Territorial Force Battalion, similar to today’s Territorial Army. Unlike some Territorial Battalions it had no direct link to a previous military unit when it was created after the reforms to the British Army in 1908. At the outbreak of the War the Battalion consisted of a large number of skilled working-class men, largely due to the efforts of the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel W.R. Ludlow who had targeted such new recruits.

It was mobilised on Tuesday the 4th August 1914, the day that War was declared on Germany. Originally the Battalion was part of 143rd Brigade and 48th Division until September 1918 when it joined the 75th Brigade, 25th Division. The Battalion was initially stationed around Chelmsford in Essex before landing at Le Havre on the 22nd March 1915. The unit fought in France and Belgium, notably the Somme in 1916 and Passchendaele in 1917, and then went to Italy in November 1917, before returning to France in September 1918 for the final advance.

Whilst no service records survive for William Amey it seems likely that he enlisted in May 1915 and went to the Front in early 1916. He won the Victoria Cross for his brave actions at Lancrecies in northern France on the 4th November 1918 (London Gazette 31st January 1919). The 75th Brigade attacked at Landrecies to secure the bridgehead on the River Sambre and the Sambre-Oise Canal (about 55 feet wide).

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that there was a cessation of hostilities a few days later on the 11th November. It was also common knowledge at the time that the end of the War would be soon. Nevertheless, the Battle of the Sambre, which turned out to be the Battalion’s last action of the War, was fiercely contested being one of the hardest fought of the final offensive.

At 6.15am on the 4th November 1918 the Battalion attacked. The 1/8th Battalion were on the left and met with stiff opposition near Faubourg Soyeres (to the north-west centre of Landrecies).

The plan was for the soldiers who attacked first to clear the passage for the 1/8th Battalion and other units who were in the second phase of the attack so that they had a smoother run and would be able to push on. However, in practice the thick fog that day meant that many German machine gun posts were not spotted and eliminated. No doubt in the general confusion of battle and not helped by the weather, Amey’s section got separated from their Company and instead joined another Company whose progress was slowed by heavy machine gun fire.

He then does three remarkably brave feats for which he is awarded the Victoria Cross.

Firstly, he led his section (probably about 30 men) to attack and eventually capture a machine gun post (about 50 prisoners and their weapons).

Secondly on his own without hesitating he attacks another machine gun post, shoots two soldiers and holds the rest until other men arrive to help.

Thirdly he again acts determinedly on his own in the face of extreme danger and with great disregard for personal safety. He rushes the strongly defended chateau of Faubourg Soyeres, killing two Germans and holding some 20 prisoners until reinforcements reached him.

By clearing away the last of the opposition in their area he saved many lives and enabled his comrades to successfully advance.

The citation for his Victoria Cross reads: ‘For most conspicuous bravery on 4th November 1918, during the attack on Landrecies, when owing to fog many hostile machine-gun nests were missed by the leading troops.

On his own initiative he led his section against a machine gun nest, under heavy fire, drove the garrison into a neighbouring farm, and finally captured about 50 prisoners and several machine guns.

Later single-handed and under heavy fire, he attacked a machine-gun post in a farm-house, killed two of the garrison and drove the remainder into a cellar until assistance arrived.

Subsequently, single-handed he rushed a strongly-held post, capturing 20 prisoners. He displayed throughout the day the highest degree of valour and determination.’

The citation is a factual account of his bravery. As such it does not describe the reality or horrors of warfare. It does not speak of the early morning chill; the butterflies in the stomach waiting for H-Hour to start the attack; the smoke and noise of machine gun fire all around; the confusion, and shouting, or meeting the enemy face to face who were equally afraid. Maybe with racing heart and heaving lungs, he acted quickly, perhaps instinctively, in the heat of the moment. We will never know for sure what drove him that day to make a brilliant rapid advance to capture enemy machine gun posts that so helped to secure the bridges. After a very severe fight his gallantry contributed to the capture of Faubourg Soyeres. The Battalion reached the Sambre-Oise Canal. As the main bridge had been destroyed some men crossed over the lock-gates and others used an enemy wooden bridge further north. That day many German prisoners and equipment were taken, and his conduct saved lives. He helped the 25th Division advance a total of 12 miles in extremely difficult conditions.

The next day on the 5th November the Battalion continued to advance and protected the right flank of the 74th brigade which was attacking the line of the Petit Helpe River. The Battalion advanced along the road from Landrecies to Maroilles. They met no opposition until they got to the edge of Maroilles when ‘A’ Company in the lead came under enemy fire. The Battalion was then relieved and the men billeted in houses in the area. On the 7th they were ordered to advance again through Marbaix to the village of St Hilaire sur Helpe where the Brigade faced strong machine gun fire.

The bravery shown by William Amey on the 4th November was very special. In all seven Victoria Crosses were awarded that day, including the one to 307817 Lance Corporal William Amey. Only one more Victoria Cross was awarded during the War, on the 6th November. A total of 6 Victoria Crosses were awarded to men of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment out of a total of 45,570 men who served in the Regiment during the whole of the First World War. A total of 628 Victoria Crosses were awarded during the entire conflict. Corporal Amey was also awarded another gallantry medal, the Military Medal (London Gazette 22nd July 1919). This was awarded for ‘exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land.’ Unfortunately, as is often the case with Military Medals no details exist as there is no citation. Although the evidence suggests that he was actually awarded his Military Medal prior to his Victoria Cross (for an action in 1917 or 1918).

After the cessation of hostilities on the 11th November 1918 the Battalion was billeted behind the lines at Le Cateau where it was engaged in routine tasks such as training and parades. They were then employed on salvage work at Cambrai. Towards the end of February 1919 many of the men were sent to other Battalions (400 men to the 2/6th and 2/7th Battalions, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment) and almost 300 went to dispersal centres awaiting demobilisation. The 1/8th Battalion was officially demobilised at Birmingham on the 1st August 1919.

William Amey left his battalion on the 14th December on leave for Christmas. In unforeseen circumstances he became ill and was admitted to Dudley Road Hospital for an operation and to recuperate. He first found out that he had been awarded the Victoria Cross for conspicuous and outstanding bravery when he received a congratulatory telegram from his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel P.H. Whitehouse DSO. He was presented with the Victoria Cross at an Investiture ceremony in the Ball Room of Buckingham Palace on the morning of the 22nd February 1919 by King George V.

The unveiling of the cenotaph to the gallant Eighth Battalion at Aston Parish Churchyard on the 4th September 1921 was led by Major General Sir Robert Fanshawe KCB DSO. He paid tribute to the Battalion, remarking that it was special for displaying three main characteristics:

Firstly, a strong sense of pride, comradeship, devotion and loyalty among the soldiers in the Battalion

Secondly there was a strong Brigade esprit de corps

Thirdly and the main thing was that they were some of the most determined fighters that a General could ever wish to have under his command.

Through his gallant actions Corporal William Amey embodies the spirit and fine reputation of the Battalion. By remembering him we keep alive and pay tribute not only to his bravery but also the memory of his comrades, who gave their best and did their duty for King and country, to who we owe much of our freedom.

After the War he seems to have worked as a business agent in Leamington Spa. He was a prominent member of the British Legion and had many ex-Service friends, who held him in high regard and affection. Along with other winners of the Victoria Cross he attended a special Garden Party held at Buckingham Palace in 1920 and later in 1929 the Victoria Cross Dinner at the House of Lords. He was given the 1937 King George VI Coronation Medal.

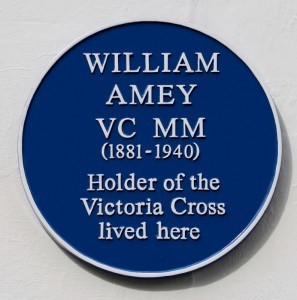

William married in 1938.Sadly the new couple did not have the chance to enjoy wedded bliss for too long as William died on the 28th May 1940 aged 59 at Warneford Hospital in Leamington Spa. His funeral was attended by two other Victoria Cross holders, Mr H. Tandey and Mr Arthur Hutt. As a mark of respect befitting his bravery he was buried with full military honours at All Saints Cemetery, Brunswick Street in Leamington Spa. In what must have been a deeply moving ceremony his coffin was draped with a Union Jack, six soldiers acted as standard bearers, and a trumpeter sounded the ‘Last Post’ and the ‘Reveille’ at the graveside. Wreaths were laid for the very gallant soldier, dear friend and a great gentleman. A carving of a Victoria Cross is worked into his gravestone. Rightly his memory lives on today. In recognition of his Victoria Cross in October 2015 Leamington Town Council sponsored a Blue Plaque to be placed on the house where he lived (13 Willes Road).

Corporal William Amey epitomised the fighting spirit of the Birmingham raised Battalion which was summed up in a poem by J. Trevannion-Foster (The Battle of Beaumont Hamel July 1st, 1916. A Poem dedicated to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment)

Oh! Citizens of Birmingham,

For your motto was their war cry:

“Forward, lads, for good old Brum’’