Much has been written about Birmingham and the West Midlands in the Great War and in this chapter Professor Carl Chinn and students from Perry Beeches Academy look at certain events and aspects of life at the time in our area.

Birmingham Women Munitions Workers

It was 1914 and the war had just begun. At this time, men had to take a stand from the age of 16 and go and fight for this country but who was to keep things running back home?

Women, yes women!

Women who had always been expected to stay at home and clean, cook, and look after the children. Despite this view of married women, however, many of them had always worked in the industries of Birmingham and now in the difficult times of the war even more had to go and work. This opened the doors for woman to be regarded in a more positive way and as a result in 1918 women over 30 got the opportunity to vote. This was the start of changing the typical stereotype of how women were perceived. Further reforms came in 1928 when all women over 21 received the vote, on the same terms as men. This brought political equality, although women are still fighting for other rights.

Birmingham’s women played a major role in the war effort as the city was a significant centre of manufacturing. At the time of the war, Birmingham was known as the city of a thousand trades, and its citizens made many different things, ranging from guns to buttons and chocolate to jewellery. When the war came along, making things like chocolate and jewellery was not the first priority. The government had to win the war and to make the needed munitions many factories were turned over to wartime production. One of the most important factories was the BSA (Birmingham Small Arms Company), located in Small Heath, where they made things like rifles and machine guns.

Another extremely important factory was the Kynoch’s ammunition in Witton just by where Aston Villa play today. Surprisingly both of these factories employed many women. Another place where many women worked in important roles was the Mills grenade factory in Hockley and women made an important contribution to making aeroplane parts at the Longbridge car factory.

In my opinion, Britain would not have been able to win the First World War without women doing their part and by doing so it opened doors for them especially in the political aspect. The important work of women in the First World War began to challenge the stereotypical view of women having to stay in their homes.

I think having this knowledge and learning about the women’s part within the war helps me to understand how significant they were for future generations of women in the work places and politics. Now I know about what these women did I think I have gained knowledge and inspiration, which I can take on further as a young woman.

Women workers at the BSA in the First World War. They were proud of ‘doing their bit’ making aeroplane parts, Lewis guns and military bicycles.

Written by Panashe

Birmingham’s Factories in the Great War and a visit from the King

It was March 1918 – a few months before the end of the First World War – and a group of journalists from British, American and Dominion newspapers visited Birmingham as it was the metropolis of the United Kingdom’s munitions industry. They spent a week in and around the city, visiting various works, and they were staggered at the colossal scale of Birmingham’s wartime production.

‘Its immensity is beyond calculation’. You work here—work night and day, without talk, with sleeves rolled up, and your shoulder to the task.’ So vast were the operations that ‘this industrial epic will never be written, for the simple reason that no man is equal to the task. There is an article in every workshop, a volume in every trade.’

In each and every hive of industry, work proceeded ‘ to the roar of the furnace, the hiss of escaping steam, the rhythmic throb of the engine, the crash of hydraulic presses, the metallic ring of stamping machines, and the clatter of lighter operations at the benches’. The minds of the journalists were left with ‘nothing but confused impressions’.

But out of this welter of ideas, imperfectly grasped and imperfectly correlated, emerge two very distinct conceptions—one of immensity of effort and output and the other of the power of organisation’.

No turn of a kaleidoscope had ever produced a more startling change than the total conversion accomplished in Birmingham for the munitions needs of a total war. Jewellers made anti-gas apparatus and other material; firms noted for their art productions manufactured an intricate type of hand grenade; cycle-makers devoted their activities to fuses and shells; world-famous pen-makers adapted their machines to produce cartridge clips; railway carriage companies turned out artillery wagons, tanks and aeroplanes; and the chemical works attended to deadly T.N.T.

Other factories and workshops manufactured shells, fuses, rifles by the million, Lewis guns by the thousand, artillery limbers by hundreds, monster aeroplanes, battalions of tanks, aeroplane engines, and big guns. In fact, Birmingham had so transformed itself for the purpose of war, that ‘it is well that the world should be made aware of the magnitude and the thoroughness of the achievement’.

That remarkable transformation had been achieved early in the War; so much so that it warranted a visit by King George V on July 22 and 23, 1915. Nominally a secret visit, it gained local attention as soon as the King arrived in the City. He first went to speak to wounded servicemen at the First Southern General Hospital at Birmingham University, and thence spent the afternoon at the works of the King’s Norton Metal Company. That night the King slept in his train in the neighbourhood of Shenstone and next day arrived at Gravelly Hill for a larger programme of visits.

First came Kynoch’s works at Witton. According to Reginald H. Brazier and Ernest Sandford in their book Birmingham and the Great War 1914-1919 (1921):

Though it was obviously impossible to see the whole of the works, which covered 50 acres, His Majesty went into a number of departments selected with the object of giving him an idea of the various stages of manufacture and organisation of the factory, which even at that early stage of the war had resulted in the output being increased 600 per cent.

It is indicative of the object of the visit to the munitions works of the city that here, as at other places, not only were the principal officials presented to the King, but many departmental managers and old servants of the various companies. In this way it was sought to show to the many thousand munition workers of the city that their efforts were of inestimable value to the nation and that they were appreciated at their real worth.

The visit by King George V to the Wolseley in July 1915

From Witton, the King was taken to the Birmingham Small Arms works at Small Heath, the Metropolitan Carriage Wagon and Finance Company at Saltley, the Birmingham Metal and Munitions Company at Adderley Park, and finally the nearby works of Wolseley Motors Limited. The King was encouraged by what he saw and the successful manner in which way in which ‘factories had been diverted from their customary civil occupations; unfamiliar labour, including that of many women and girls who previously had never seen the inside of a factory, had been brought in and trained to new occupations; and it was a subject of astonished comment how quickly this inexperienced labour adapted itself to unfamiliar tasks and how keen the women were to obtain the largest possible output.’

All the companies visited, as well as many more, played vital roles in the prosecution of a total war, but some of the biggest contracts went to the BSA, the Vickers-Metropolitan group of factories, and Kynoch’s. The latter company had been started in 1862, by an intriguing and colourful Scotsman called George Kynoch, a bank clerk from Peterhead. His business first made percussion caps in Great Hampton Street, but its operations expanded greatly when the Lion Works were opened at Witton. Alongside its cartridge huts were built rolling mills, and this feature led to the eventual takeover of Kynoch’s by ICI.

During the First World War, the company expanded to take on 18,000 workers as it contracted to manufacture each week 25 million rifle cartridges; 300,000 revolver cartridges; 500,000 cartridge clips; 110,000 18-pounder brass cases; and 300 tons of cordite. It did so successfully and during the last major German offensive of 1918, the output of cartridges reached 29,750,000 per week. These figures are even more impressive when it is taken into account that ‘there are 102 operations in the manufacture of a single rifle cartridge, and the limit of accuracy prescribed in nearly all the finished dimensions is within one-thousandth of an inch’. Bar for the cordite, everything involved in the production was manufactured in Birmingham.

As for the BSA, the increase in output of rifles was astonishing. From an average of 135 rifles made per week in the five years before the war, production was increased to about 10,000 per week; whilst output of Lewis guns rose from 50 a week, to 2,000. In addition, BSA manufactured bicycles and motor bicycles for the Army and 150,000 aeroplane parts per week.

The Vickers-Metropolitan group of factories in Birmingham also made a considerable contribution to the war needs of the nation. Tanks, aeroplanes and ‘other of the larger engines of war’ were manufactured at its wagon works; whilst 38 million fuses and large numbers of anti-aircraft shells and naval and field cases were produced at the Electric and Ordnance Accessories factories in Aston and Ward End.

As notable a contribution was made by the Wolseley Motors, which built over 4,000 cars for use in the war as well as 4,500 aero engines and sufficient engine spare parts to be equivalent to another 1,500 engines. In addition, Vickers turned out nearly 700 complete aeroplanes, 850 wings and tail planes, 6,000 propellers, over three million shells and ‘the whole of the transmission mechanism of the British rigid airships’. Finally, “nearly 300 British warships were fitted with director firing gear and gun sights made at Adderley Park and 1,000 naval gun mountings were produced there.”

In 1921, when he was made a Freeman of the Borough, the Prime Minister, Mr. Lloyd George emphasised the importance of Birmingham in a speech at the Town Hall. He declared that ‘the country, the empire and the world owe to the skill, the ingenuity, the industry and the resource of Birmingham a deep debt of gratitude, and as an old Minister of Munitions, and as the present Prime Minister, I am here to thank you from the bottom of my heart for the services which you rendered at that perilous moment.’

Professor Carl Chinn

Hall of Memory

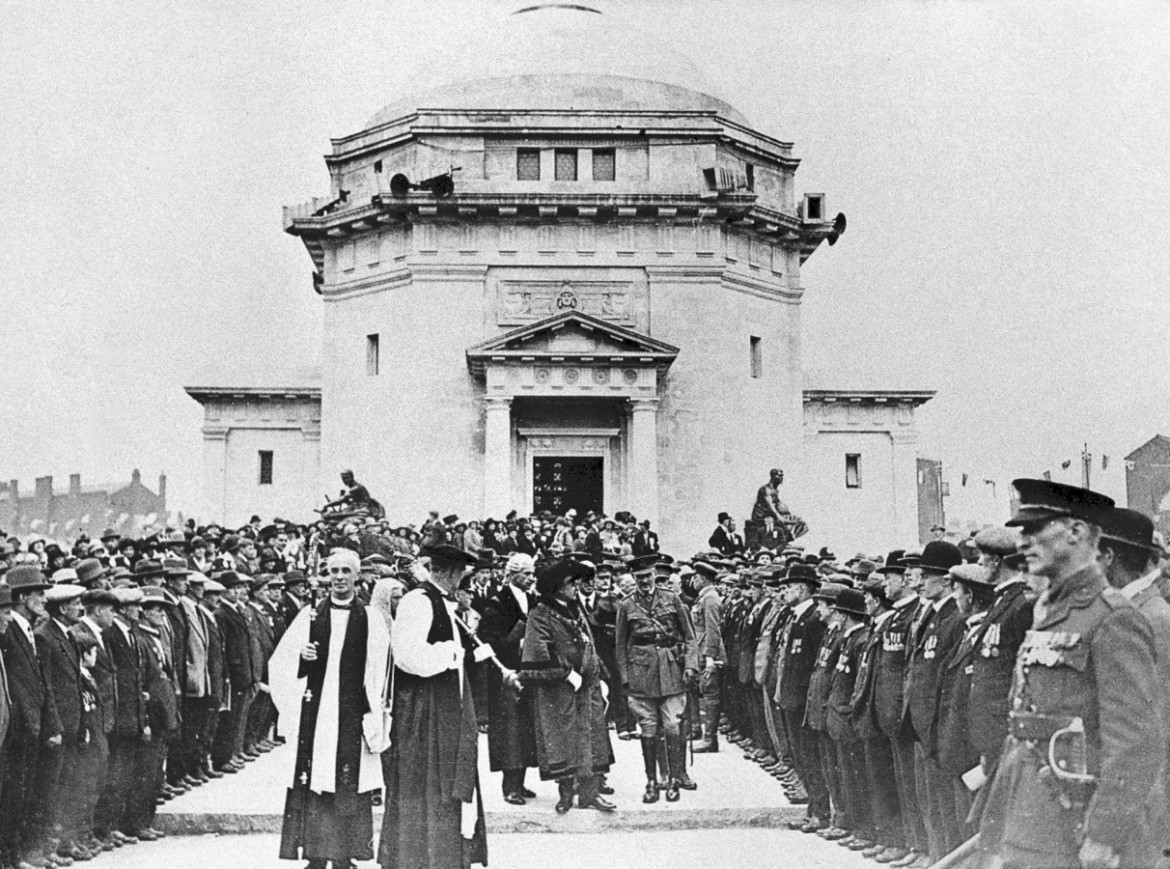

The opening of the Hall of Memory in 1925

For some of us the Hall of Memory is within walking distance of where we live although this is taken for granted. However, we visited this building for the first time in March 2015 resulting in a huge impact upon the group members. The strange atmosphere there shocked all of us as it was as if we were blasting back to the past. The value and the history within the Hall of Memory is phenomenal. The Hall of Memory is a war memorial for the individuals who had died in the tragedy of World War One. This iconic structure is a great tourism attraction. A trip to the facility helps you think about the value of those who risked their lives in order for us the people of the future.

The Hall of Memory was built to commemorate the 12,320 British citizens who died in World War One. This was a brutal event where many people lost their lives, so what is a better way to show our appreciation by contributing to these heroes who fought for our lives by documenting their names within intuitive and historic books.

In the middle of the Hall of Memory is a shrine with a bronze casket. Inside is the World War One Roll of Honour. This book distinguishes every individual who had died in the war, therefore giving them each their own identity. After 1945 a Roll of Honour was added for those who died in the Second World War. There is also cross a third Roll of Honour with the names of those who have died in campaigns since then.

The Hall of Memory is located on Broad Street, Birmingham. The structure was first opened on July 4, 1925 by H.R.H. Prince Arthur of Connaught. Around the exterior on granite pedestals stand four larger than life bronze statues constructed almost entirely by Birmingham craftsmen. They symbolise the contribution made to the war by the Navy, Army, Air Services and Women.

As we walked into the entrance on our visit our eyes were filled with the view of poppies in wreaths laid by schools and other local organisations in respect for the brave soldiers who had fought to make the world a better place.

On the walls are three designs showing different aspects of the Great War. The first is ‘Call’ and shows men leaving home to join up. It states that ‘of 150,000 who answered the call to arms 12,320 fell: 35,000 came home disabled’.

The second is Front Line. It shows a party of men in the firing line and says, ‘At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we shall remember them’. The third shows the wounded and maimed coming home. It states, ‘See to it that they shall not have suffered and died in vain’.

We felt privileged to be able to have the opportunity to set foot in such an historical place. We will always be grateful to those who are remembered in the Hall of Memory.

Written by Sorena and Jade

The Zeppelin Raid on the Black Country in 1916

The Zeppelin Raid was a key part of the First World War in the West Midlands, due to the fact that it was the first ever air raid in that region. On January 31 1916, nine airships or Zeppelins left their bases in Germany where they were ordered to bomb Liverpool and shock the British by the long range of the attack. The year before Zeppelins had begun their raids on London and it was thought that it was impossible for them to reach as far as Merseyside. The enemy did not reach their target because of the horrendous weather with mist and fog surrounding the area. Having lost their way, they dropped their bombs on several English towns, mostly in the Midlands and not on Liverpool. Chief amongst them were Tipton, Wednesbury and Walsall in Staffordshire.

As the Zeppelin Raid flew on, more bombs were being dropped on a place called Bradley, where two civilians called Maud and Frederick, were killed as they were courting on the bank of the Wolverhampton Union Canal. Then at 8:15pm, the L21 let loose bombs in several parts of Wednesbury around King Street, near to the Crown Tube Works, at the back of Crown and Cushion pub, and in High Bullen and Brunswick Park Road. Another fourteen people were killed: four men, six women and four children.

An adult and child looking at the damage in Walsall caused by the zeppelin raid of 1916; thanks to Walsall Local History Centre

Walsall was finally bombed. The first bomb landed on the Congregational Church on the corner of Wednesbury Road and Glebe Street. The Zeppelin dropped bombs in the grounds of the Walsall and District Hospital and Mountain Street and its final bomb fell in the Centre of Walsall, killing three people. One of the three was the Lady Mayoress of Walsall, 55-year-old May Julia Salter, who was rushed to hospital suffering from severe wounds to the chest and abdomen, although she later died of shock and septicaemia.

The specific Zeppelin that caused all this death and damaged was one called the L21. It was ginormous at 53 feet long and 61 feet broad. It was capable of reaching speeds of up to 60 miles an hour. It was captained by Max Dietrich, the uncle of famous singer/actor Marlene Dietrich who was successful for 50 years, from 1920s-1970s.

We did not know about the zeppelin raid until we started to research it for this project. We learnt how the Zeppelin raid had an impact on the West Midlands and its people. However, this raid was only a small raid compared to those that would attack Birmingham in the Second World War.

Written by Nico and Nathan